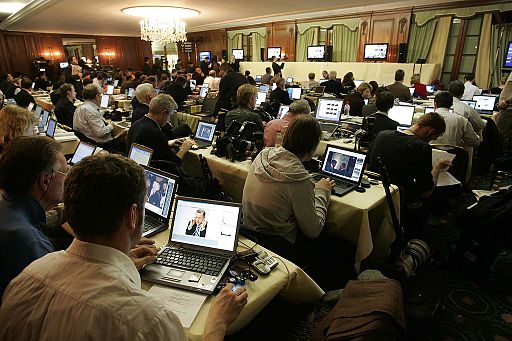

Photo by Kai Mörk, freely licensed under CC BY 3.0 (Germany).

As a researcher, one of the things that has been most interesting to me over the recent few months is that I’ve noticed an increase in the number of articles relying on investigative journalism. Many larger newspapers have some sort of investigative unit, like the Boston Globe’s deservedly celebrated Spotlight Team.

But it’s been historically unusual to see skimcoat newspapers – that are more commonly slipped under hotel bedroom doors for business travelers – begin to do deep investigative research projects. It’s another reminder that that the information geeks of the world – we researchers – are the most important players speaking truth to power.

In journalism and in fundraising

We Third Sector professionals have a lot in common with our cousins in the Fourth Estate. At the most honorable level of our craft, we each search for the facts, for the answers to the questions that – we hope – ultimately make our society, our world, a better place.

I’m not saying that the highest ideals are always there, in either profession. I’ve seen sloppiness both in articles and profiles that made me despair. Especially when the possibility for goodness – not even greatness, just plain goodness – was so easily within reach in the author’s final product.

But anyway.

The other thing I’ve noticed happening in both sectors is the rise of collaboration.

In the Third Sector, foundations are collaborating: If you listened to our podcast last week, you will have gotten a taste of Elizabeth Roma’s and Angie Stapleton’s upcoming Apra webcast on the transformational collaboration happening in philanthropy. Foundations, individuals, nonprofits, NGOs and the public sector are building a fast-growing number of giving collaboratives, especially designed to efficiently and strategically pool a lot of money to solve the most intractable problems in the world.

Foundations love collaboration, too: It’s been true since at least the 1990s that foundations have favored making grants (for example) to universities and other large institutions that develop inter-departmental or cross-disciplinary initiatives. Individuals and companies also favor supporting initiatives involving the best talent working together across two or more institutions, because it has always made sense to crowdsource intellectual abilities.

Collaboration supports our knowledge foundation: And that describes our profession perfectly, too. One of the things I have always loved about our profession is our willingness wild-eyed fervor to share best practices, great resources, and spreadsheet templates. Recently my colleague Grace wrote an article about that kind of collaboration within our own team which we find crowd-sources information to the benefit of our clients (as well as satisfying our own thirst for knowledge).

Journalism has taken a big credibility hit in the past year or so, but through collaboration the Fourth Sector is starting to find its way forward.

It used to be that journalists operated less collaboratively because getting “the scoop” was the surest way for one to get ahead. But working alone leaves you open to seeing only one side of the story, as well as potentially missing key facts or having access to the right sources.

Thanks to the internet, recently a new type of journalism has emerged – collaboration on a large, multinational scale yielding stories (and help on the research behind them) that no one journalist could possibly tackle on their own.

For example, last year the International Consortium for Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) published the epic-ly-scaled “Panama Papers” project which is still ongoing. More than 190 investigative journalists in 65 countries are working on that and many other projects together. It’s collaboration on a massive scale.

Reporters are also collaborating with volunteer citizen journalists – professional researchers like us and regular members of the public – to help them sift through piles of information that no one person can tackle alone. White House reporter Christina Wilkie’s #CitizenSleuth project has mobilized thousands of volunteers in a crowd-sourced effort to parse out donors to the presidential inauguration campaign/fund. The citizen sleuths found revealing results within hours of the Google doc being made public.

ProPublica “Reimagined Engagement” with the public it serves, by enlisting citizens’ help in sharing letters they received from members of Congress about the Affordable Care Act and its replacement, in order to fact-check what people were being told. ProPublica also put out a call for help to research the backgrounds of over 500 political appointees who were secretly installed in ‘beachhead’ positions across every major federal agency.

Because of the general undercurrent of mistrust in published media, it’s comforting that the rise of collaboration can also provide a sense that there’s more fact-checking happening generally in the news that comes to us. It’s logical to think that, if only one person’s name is in a byline, there’s a possibility they could just be skimming their copy to beat a deadline. But if more than one person has their name attached to an article, there’s a sense that quality control is increased.

This is true for prospect research, too. Increased collaboration, crowd-sourcing resources, and fact-checking each other is a way to learn and improve our own quality. We may “speak” differently from journalists, and so is the power we speak to. But it’s no less important for any of us to get our facts right.