Discussion about Social Impact Bonds is really hot right now. SIBs have the ability to reward nonprofits for being innovative and for achieving measurable and replicable success. But will they remove funding that would have been philanthropically given? And will smaller nonprofits be left out in the cold?

To find out more, I attended last week’s Social Innovation Forum hosted by Root Cause. The featured speaker was Jeffrey Liebman, Malcolm Wiener Professor of Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. After Liebman’s opening remarks, a panel of experts discussed SIBs and how they might affect nonprofits.

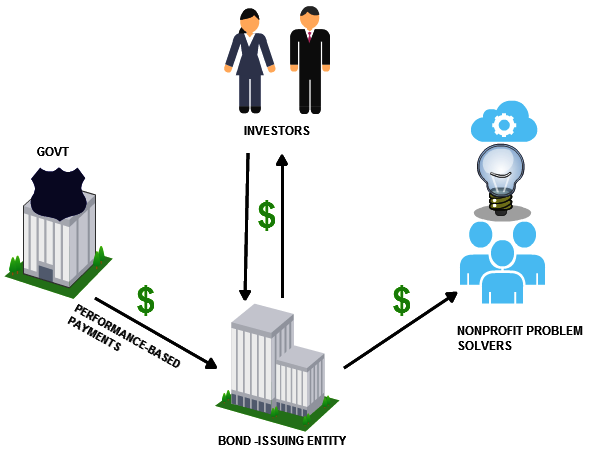

Liebman provided a very simple graph to illustrate the flow of money in a SIB, which looked something like this:

Here’s how it works in a nutshell: A nonprofit (or more probably, a collaboration of nonprofits) works with a bond-issuing entity to raise funds to solve a social problem. Investors are approached by the bond-issuing entity and the investors provide working capital to the bond-issuer. Investors are guaranteed a rate of return if the project succeeds, and the return on investment is likely gauged to the project’s risk of success. (If the project fails, investors lose their money). When the project is completed and has met performance targets, the government pays the bond-issuing entity, which pays back the investors their initial investment plus interest.

It’s a win-win-win.

- The problems solved are ones the government would have funded anyway (reduced recidivism, for example, or after-school reading programs). But with SIBs, the government only pays when there is demonstrated success, lessening government waste.

- Venture philanthropists and foundation leaders have a creative tool for their investment portfolio to both fund programs and reap a return on their philanthropic investments which they can then use to seed another venture.

- Nonprofits with proven success in their field of expertise have another pool of potential support to draw from.

Jeffrey Liebman calls SIBs a “Pay-For-Success” program, and it’s easy to see why. As he explained, SIBs improve nonprofit performance and lower cost to the government; they accelerate the adoption of new solutions that are broadly replicable; and there is more rapid learning of what works and what doesn’t.

So what are the problems with a Pay-For-Success program?

Well, there are a lot of nonprofits out there and competition for dollars is already fierce. According to the National Center for Charitable Statistics, over 1.6 million charities registered with the US IRS in 2011. Granted, about 100,000 are foundations and a little over 500,000 are professional associations, fraternal organizations, chambers of commerce, etc. Still, that leaves about a million nonprofits vying for philanthropic support and not all of them will be candidates to participate. Also, SIBs won’t work for every type of nonprofit.

The likely participants will be collaborations of nonprofits working together to creatively solve a specific social problem. They will provide new solutions with the potential for high net benefits and will be able to provide measurable outcomes. The populations they serve will be well-defined and there will be a reliable comparison group.

Won’t this mean dollars formerly allocated to philanthropy will be used for SIBs?

Panelist Tracy Palandjian of Social Finance Inc. commented that SIBs wouldn’t cannibalize philanthropic dollars because a foundation could invest in SIBs from the 95% of their investment corpus rather than from their 5% annual distribution. SIBs become both another investment vehicle and a way to further a foundation’s vision and mission.

One forum participant, a representative of a foundation observed “isn’t it the point to cannibalize money from underperforming nonprofits to fund those that are producing results?”

What is clear is that all nonprofits – those struggling for money merely to survive as well as those that are well-established – will need to start measuring their impact on the communities they serve if they aren’t already. Today’s donors already expect to see a nonprofit’s results clearly outlined but a social impact bond-holder will require it, and it will be the bond-issuer’s job to track the venture’s success. Will there be a move within our industry to set standards for the metrics that are tracked?

As a professional in this field, the idea that we researchers will be helping our organizations create the most logical metrics and use that data to improve service delivery is exciting to me. But as cool as that is, and even though there is already one test-tube SIB in place in the UK, I can’t get too excited yet.

The biggest roadblock?

The biggest problem could be politics. Most projects that a SIB would cover would likely be funded over one or more election cycles. What happens if the next person in office decides that they don’t want to honor the previous office-holder’s bond agreement?

In an era where Congress can’t seem to get it together over the simple task of running its daily business, what chance does a new initiative – however fiscally sound, however cost-saving – have?

Governor Deval Patrick of my home state of Massachusetts was the first to formally seek to explore SIBs in May of this year. We’ll see if he leads us to create the first one in the US.

RootCause wisely videotaped some of the key segments of this fascinating forum. Have a look to learn more!

Read more here about Social Impact Bonds and Impact Investing (which apparently goes back to the Civil War!) from the Harvard Business Review’s blog article written by Chris Meyer and Julie Kirby.