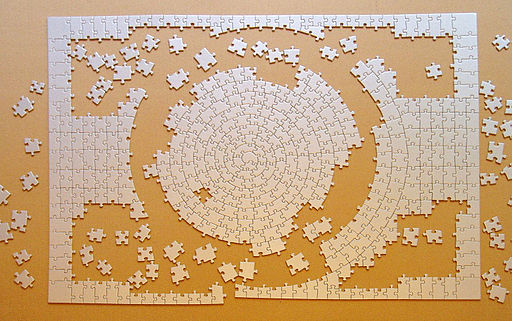

It’s a useful exercise to think about our society as a puzzle where governments, and government-run operations, and businesses, and civic life, and religious organizations, and educational institutions and hospitals and charities and NGOs each, interdependently, make the picture of society whole.

It’s a useful exercise to think about our society as a puzzle where governments, and government-run operations, and businesses, and civic life, and religious organizations, and educational institutions and hospitals and charities and NGOs each, interdependently, make the picture of society whole.

We’re so busy trundling through each of our own parts, though, that we take the others…well, maybe not entirely for granted, but as if they’re permanent fixtures. I know that I’ve always assumed that things like restaurants and cute little shops and, you know, the post office would just always be there.

Now that COVID-19 has darkened our lives in uniquely individual ways like the fires have turned West Coast sunshine to midday night, it becomes harder for us to see each of those puzzle pieces that are farther afield. All of the everything going on in our own world obscures the picture on the box that reminds us what the integrity of the whole looks like.

We’re cut off, and it’s making us focus on our own piece and less on the whole.

As a fundraising intelligence professional, my work-life has been focused on identifying and bringing to life current and potential donors in a way that faithfully and ethically tells their story and motivates a fundraiser to begin (or continue) a relationship with that donor.

I’ve always deeply believed in the power of philanthropy and the good it does on both ends – making the world a better place and giving donors the opportunity to feel how amazing it is to do that.

And I still believe that, but if you read my article from a few weeks ago, you’ll remember that lately I’ve been concerned that prospect development has had a role to play in missing out on the next generation of donors. Not entirely, of course, and I know that our profession (and our company) is doing our part to help organizations find mid-level and future major donors quietly putting up their hands.

But still. I’m working harder than usual lately on trying to see beyond my piece.

And now that I’ve pulled the focus out a bit, I realize that there’s an even bigger picture which I’ve struggled against for over a year and tried to ignore because it’s too difficult to think about.

I know the nonprofit sector is by no means perfect. It’s hard to attract the level of talent and experience for jobs that for-profits can because nonprofit salaries are lower. Small nonprofits don’t have the bandwidth to compete with larger ones for much-needed funding. Large nonprofits are bureaucratic behemoths that have lost the ability to be nimble.

But large or small, every single nonprofit has to sing and dance for their supper. Every. single. day.

Every single day nonprofits are called on to Show Their Impact.

Be Donor-Centered.

Meet State Laws. Federal Laws. International Laws.

Every day they have to jump through ridiculous hoops to gain institutional funding that, in the end, may not even cover the cost of gaining, tracking and reporting the donation.

As a sector, we’re working really hard – really hard – with fewer people because of furloughing and permanent separations, to secure the next gift just to survive right now. And there’s just so much wealth out there.

It’s exhausting. It’s not just. And it’s not tenable.

In our time of greatest need, Chuck Collins, director of the Program on Inequality at the Institute for Policy Studies asks in his opinion piece for The Guardian, “Why aren’t the rich giving more?” Many of the philanthropists that fund nonprofits are richer than ever before – some are richer because of the pandemic. He reminds us that the wealth of members of The Giving Pledge has nearly doubled since February.

Collins writes:

Many have stepped up to give during the pandemic. But their giving is not keeping pace with their exploding wealth.

This leads to the second problem: in all likelihood, most of what they give away won’t go to on-the-ground charities, but to private family foundations often controlled by wealthy heirs and their advisers. Instead of supporting charities on the frontlines of problem solving, these billions end up sitting in tax-advantaged intermediaries.”

The Chronicle of Philanthropy has just started a 5-part series specifically to discuss what’s next for the philanthropy sector, and I highly recommend it. I’ve long admired the work of Lucy Bernholz, director of the Digital Civil Society Lab at Stanford University’s Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society, and her article (part 3 of the series) is a barn-burner. In “Let’s Dismantle Toxic Tax Policies That Feed Big Philanthropy” Bernholz writes:

In the United States today, a toxic tax code permeates our soil and prevents us from growing into a more equitable society. Our current tax laws starve our schools, hospitals, transit, and elder-care systems. They allow individuals to become trillionaires and corporations to pay nothing. They enable the amassing of philanthropic fortunes so large that people turn to them when government efforts fail.

For decades, these policies have concentrated financial benefits on the white ruling class while extracting wealth from low-income Black and brown people. The pandemic is the “big reveal” of the truly shared nature of these systemic inequities.”

As someone who deeply cares about our sector and who is steeped every day in understanding wealth, it’s been increasingly difficult for me during these past 6 months not to get angry and frustrated while learning about any non- (or weakly-)philanthropic individual’s increasing billions – knowing that it would require almost no sacrifice for them to significantly create lasting change for the world. Or even one piece of it. Especially when so many others are doing so much.

Nonprofits shouldn’t have to sing for their suppers. They should be funded to fill the gaps in society, and there should be fewer gaps to fill every year as we work toward a healthy republic, not more and more.

Our professional association boards and leading practitioners should take seriously what the philanthropy scholars, experts, and writers are saying now; consider the many solutions they’re offering; and join with members of congress who care about fixing this broken system. This sector is vital to making our society one that makes sure everyone – not just the wealthy – thrive. We’ve got to make it work.