It used to be that it wasn’t all that often that a bombshell like the Panama Papers dropped during your professional lifetime. The practice of accidentally or purposefully sharing sensitive, confidential, or downright incendiary information is becoming lots more commonplace lately.

It used to be that it wasn’t all that often that a bombshell like the Panama Papers dropped during your professional lifetime. The practice of accidentally or purposefully sharing sensitive, confidential, or downright incendiary information is becoming lots more commonplace lately.

Meanwhile, there are people and companies and governments struggling worldwide with questions of how to maintain the privacy of individuals’ personal data, and just who should have access to it. There’s the desire by some to be erased entirely from the internet (sorry, but good luck with that). Cross-border information-sharing agreements, like Safe Harbor and its next-gen, the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield, hold little consumer confidence.

IT’s a brave new world, and we’re all trying to sort out what relationship “information” and “technology” should have. As Chris Carnie, chairman of UK-based prospect research consultancy Factary points out in a recent blog post,

We live in interesting times, privately.

Confusing, contradictory times, when lawmakers require us to lock-down data whilst revealing their intimate thoughts on Twitter. Times when it is OK for a dominant search engine to track our billions of tiny searches, for our wrist watch to measure and transmit our sleeping and walking in the name of fitness. Times when we choose to tell our life stories in Facebook.”

A 2013 study by the Pew Research Center found that young adults were less tolerant of governmental collection of personal data available electronically than all adults as a group, but nearly 50% of Millennials felt comfortable with a company doing the same thing if they got something in return (as compared with 30% of all adults as a group). A broader 2015 study showed that we Americans may want or expect privacy, but the reality is that most of us are fairly resigned that we’re not really going to get it ever again. And at the rate we share personal details on social media, we’re our own worst enemies.

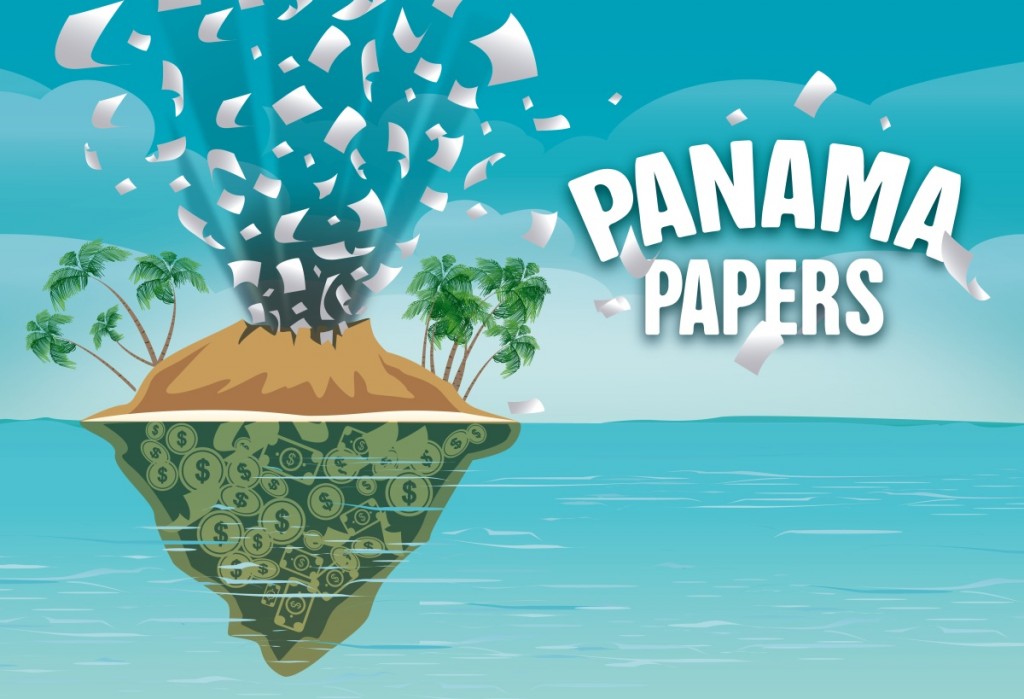

So it may just be the beginning of an era that will mean an increasing number of Wikileaks and Snowden-style revelations will get exposed to the public. For people who study the movement of wealth and the wealthy, the uncovering of the Panama Papers is a Pandora’s Box opening a portal into the parallel universe of secret deals, money laundering and huge assets crossing borders.

If you’re not familiar with what the Panama Papers are, there’s lots of information available for you to get caught up. Some of the best resources are found here at the Center for Public Integrity’s project site, ICIJ – the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. They’re the ground-zero collaborative investigating and reporting on the more than 11.5 million legal and financial records leaked by an anonymous tipster to the German newspaper Süddeutsch Zeitung over a year ago.

These records, spanning about 40 years, were obtained from a Panamanian law firm called Mossack Fonseca. MF sets up off-shore companies for companies and individuals. These entities may be seeking to avoid or minimize tax, provide untraceable ways to do illegal business activity, or simply want to do business in a country external to their primary headquarters or residence. They could be the assets of a billionaire who is running from the law or running for president.

There’s nothing illegal about creating offshore entities. It’s what happens once one is set up that sets off alarm bells.

Nonprofits in the UK and Europe have long been concerned about the relationships they form with large donors. If we ask Mr. X for a donation large enough to put his name on our research vessel, or if we recruit Ms. Y to serve on our board – could that open us up to liability or reputational damage? Are they secretly running guns? Involved with a company that is a massive polluter?

It’s not that we don’t look into those things over here, but my experience is that European prospect researchers spend more time, effort, and heartache doing (and talking about doing) due diligence research than we tend to do here in North America.

The Panama Papers and due diligence

To make the Panama Papers information transparent to the public, the ICIJ created a searchable, free database of over 320,000 offshore entities. You can search people and companies in more than 200 countries worldwide.

Once you search for an individual or company in the Panama Papers database you’re given the ability to search for more information on that company at another site called OpenCorporates. OpenCorporates is another free (and incredibly useful) database of companies – and directors – worldwide which was set up as an open access project to further the availability of information about companies and encourage their corporate transparency.

The existence of this database might present prospect researchers with a bit of a dilemma. Weighed in the balance:

- The information was obtained illegally (but leaked to expose corruption).

- Are there privacy issues to consider regarding those 320,000 entities named?

- How does the availability of this information weigh against our responsibility to protect our nonprofits’ reputations and balance sheets (and the relationships with the majority of donors who are not gun runners)?

For me, I can’t overlook a resource that could protect and inform my clients. If their prospect has set up shell companies in Ras al-Khaimah, China, and the British Virgin Islands, they need to know about it.

Also, these journalists have created a huge resource of data, white papers, and articles specifically to educate those of us interested in wealth creation, distribution, and movement. To do my job well, I want to understand how offshore holdings work so that I know how to recognize clues when I research and advise clients if I see potential risk.

What’s your thinking? Have you used the Panama Papers database? What have you found?

RESOURCES

About the ICIJ (from their website: https://www.icij.org/about)

“The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists is a global network of more than 190 investigative journalists in more than 65 countries who collaborate on in-depth investigative stories.

Founded in 1997 by the respected American journalist Chuck Lewis, ICIJ was launched as a project of the Center for Public Integrity to extend the Center’s style of watchdog journalism, focusing on issues that do not stop at national frontiers: cross-border crime, corruption, and the accountability of power. Backed by the Center and its computer-assisted reporting specialists, public records experts, fact-checkers and lawyers, ICIJ reporters and editors provide real-time resources and state-of-the-art tools and techniques to journalists around the world.”

Graphics by VectorOpenStock.com

WE’RE READING

The Hidden Wealth of Nations, Gabriel Zucman

Tax Havens: How Globalization Really Works, Ronen Palan, Richard Murphy, Christian Chavagneux

Treasure Islands, Nicholas Shaxson