Hierarchically speaking, fundraising intelligence doesn’t usually sit at the top of any nonprofit organization’s organization chart. In fact, the most junior member of the Research team usually inhabits one of the boxes at the bottom of the chart, in my ongoing study.

Hierarchically speaking, fundraising intelligence doesn’t usually sit at the top of any nonprofit organization’s organization chart. In fact, the most junior member of the Research team usually inhabits one of the boxes at the bottom of the chart, in my ongoing study.

But I’ve also known for a while that org charts can be deceptive. It’s the culture of a place and the specific people in the boxes that are usually the drivers of who has the ‘power’ and who doesn’t. Certain people, regardless of box geography, are able to reach beyond borders.

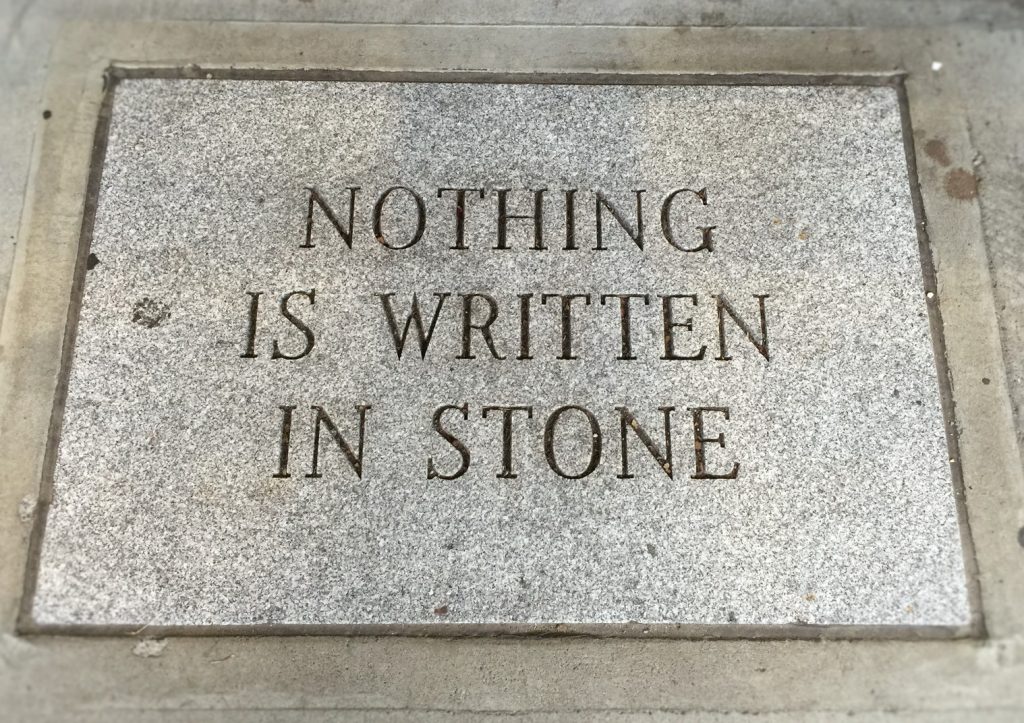

Leaders that hire skilled, talented people and then let them get on with their jobs – with minimal interference and maximum support – tend to engender more loyalty and have lower staff turnover. Those people, regardless of box, can lead from the top, from the middle, or from that bottom box. Nothing, for them, is written in stone about what they can accomplish or whether or not they can be seen as a leader.

Tom Kalil is the author of a paper published by MIT Press called “Policy Entrepreneurship at the White House; Getting Things Done in Large Organizations.” Kalil is now Chief Innovation Officer at Schmidt Futures (as in Eric Schmidt of Google fame), but he worked at the White House for 16 years helping to “design, launch, and sustain dozens of science and technology policy initiatives” over the course of those years at the Office of Science and Technology Policy (an Office which has been director-less since January of 2017).

In Kalil’s article are outlined “Twelve Maxims For Getting Things Done.” That description sounds pretty simplistic, and actually, when you read the article, the maxims are very straightforward. But don’t dismiss them because they sound basic. Every strong-functioning fundraising office I’ve ever seen uses them, whether they do it consciously or just by luck.

This week and next, I want to take you through the maxims to illustrate how they can be used in fundraising intelligence to lead. I’d be honored if you’d read this week’s and next week’s articles, but if you want to go straight to the source instead, I won’t be disappointed – it’s a don’t-miss article.

Maxim 1: Have an agenda, rather than merely reacting to the agenda of others or to external events

Prospect research, fundraising data science, and relationship management all have defined purpose and benefit within a fundraising office, but frequently we don’t plan out an agenda for how we want to deploy our strengths. Within those teams (or if you’re a team of one) you can also have a personal agenda for how you want to comport yourself or for what you want to achieve or how you want your role or experience to grow. What’s your agenda?

On a more practical note, do you bring an agenda when you meet with your supervisor? Back when I inhabited one of the lowest boxes, one of my former supervisors tipped me off to bring a meeting agenda with me each time I had the opportunity to meet with the tippy top brass. It seemed overly formal at first but sent the right signal and made a difference in how I was viewed. That agenda demonstrated without saying a word that her time was important to me, and mine was valuable as well.

Maxim 2: Ask interesting questions

Obviously it’s very important to have the answers to questions that your peers, supervisor, or leadership ask, but the questions you ask also say a lot about how much you’re listening, how interested you are in the topic, and what opportunities you can help build (or pitfalls you can help avoid).

Asking questions just for the sake of showing your knowledge isn’t the same thing, though. Nobody wants to hear a blowhard asking a question simply to show off. Interesting questions are the ones that help other people see points that they wouldn’t have without your unique perspective.

Maxim 3: If you want someone to help you, make it as easy as possible

When I think about this maxim, the first thing that comes to my mind are the research request forms of old that used to take frontline fundraisers 15 minutes to fill out in order to obtain 5 minutes’ worth of research time. Ask yourself – what do we make unnecessarily difficult, and how can we simplify those processes?

One of my primary goals when we partner with a client on a research department audit is to help figure out ways to increase communication between the fundraising intelligence team and their “clients.” If there’s a blockage, we pull apart the entrenched ways of doing things to figure out what the simplest and most efficient do-able ways of doing things can be. Within the limitations that always exist, making it harder for people to communicate makes no sense to me.

Maxim 4: Work from the top down and the bottom up

Buy-in is incredibly important. It’s no secret that if you want a relationship management system (or a database conversion) to work, you have to have buy-in from the “big boss” and the lowest-rung fundraiser, from the data-entry assistant to the database administrator, and from everyone in between.

Leading from behind can be frustrating in those situations – and in any situation that means big change for people to adjust to – but it’s also a way to gain trust, show leadership, and build collaborative structures and teams.

Maxim 5: Understand the pros and cons of multilateralism, minilateralism, and bilateralism

This is just a fancy way of saying that you need to understand the benefits (and pitfalls) of building relationships or collaborating at different levels. And, of course, the more people you interact with and build relationships with, the farther you’ll go in your career.

Multilateralism is building relationships within a large group structure. This can mean speaking at a conference; serving on a volunteer committee at AFP, Apra, or a chapter; or writing for a professional publication.

Minilateralism could be setting up or participating in a learning/training day with your Research team and a speaker; or getting your university’s research team together with another team across town to share how you use resources.

Bilateralism is picking up the phone to call a fundraising data scientist across town to have lunch or coffee. Or meeting with a real-estate-agent-turned-frontline-fundraiser at your organization to pick their brain about real estate trusts.

Maxim 6: Increase the likelihood of follow up

In his article, Kalil focuses on getting other people to follow up, but I think it’s really important to stress that we need to be able to be relied on to do the same.

He suggests asking the person you’re dependent upon for action to specifically state when the task will be complete, and to send a follow-up email with that date in it as a reminder to them. Kalil says that keeping those dates in your calendar is important to keep track.

If people are habitually late or not doing what they say they will (or when they say they will), instead of getting frustrated, try to figure out why they’re not meeting their deadlines. Perhaps there is an unseen impediment (technology? Unwilling supervisor?) to getting the job done.

If you’ve tried to figure out what the blockage is and aren’t getting anywhere, Kalil suggests something I would never recommend – doing an end run around the person and meeting with their boss. No – a thousand times no. Meeting with your boss is a much better idea. Maybe that person knows what the blockage is or can provide you with alternate strategies.

Next week I’ll cover maxims 7-12. In the meantime, I’d love to hear your thoughts on these so far.