This month we welcome HBG’s Angie Stapleton who has become quite the expert on tech startups. Angie navigates us through the terminology around startups, shows how and why unicorns fly so high, and gives us insight into what their value might mean for fundraising.

When I was a little girl, unicorns were everything. I mean, if you didn’t have a Lisa Frank unicorn lunch box, hello, you may as well just go back home. Today, a new kind of unicorn reigns king… tech start-ups.

When I was a little girl, unicorns were everything. I mean, if you didn’t have a Lisa Frank unicorn lunch box, hello, you may as well just go back home. Today, a new kind of unicorn reigns king… tech start-ups.

In recent years, tech firms with valuations of $1 billion have become all the rage, the Silicon Valley darlings, the UNICORNS of the investment world. In fact, investors have even come up with a new name for tech firms whose values rise above $10 billion… DECAcorns. I’m guessing this is because “unicorn” just didn’t encompass enough magic and whimsy.

With news of these fairy-tale creatures running loose (in what seems like herds!), I started to ask: what does it take to be a unicorn? Can something named after a mythical creature be too good to be true? And, most importantly, what does this mean for development professionals who are pinning their hopes of a major gift on unicorn-produced prospects?

Tech Firm Valuations… more art than science

So, I started this process by asking how companies even receive unicorn status. According to CB Insights, there are now a record 152 unicorns, with a combined valuation of $529 billion. VentureBeat expands their industry segments just slightly and reports those numbers even higher, with 229 unicorns raising a $1.3 trillion valuation. We’re producing unicorns at a rate never seen in history. So, what is driving it?

Investors searching for the next big thing.

I was looking for an algorithm, some sort of equation, to tell me how to look at a company (their revenue, forecasted growth, etc.) to factor into their valuation. Turns out, it’s not that simple.

We know how a company receives a dollar-amount valuation: for the sake of easy math, if an investor pays $100 million for a 10% stake in a firm, that gives a company a valuation of $1 billion. What is much harder to determine is how an investor and the company determine that $100 million is worth a 10% stake.

That’s the magic. That’s where unicorns are born.

In most cases, this gray area is what has allowed recent tech valuations to balloon to such staggering – and some would say, unrealistic – heights in recent years. Bloomberg explains in “The Fuzzy, Insane Math That’s Creating So Many Billion-Dollar Tech Companies”:

Since private tech companies often lack earnings or enough historical data to inform projections—or… any significant revenue—investors can’t rely on the metrics available.”

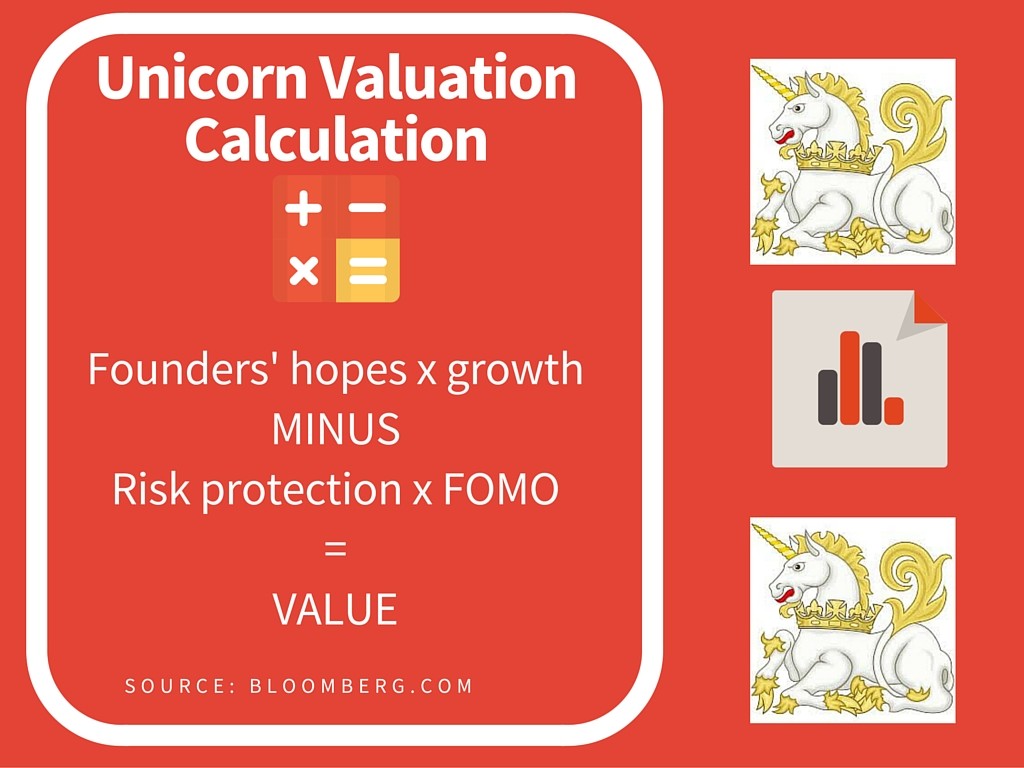

The article goes on to give the following equation, essentially pinning a valuation to four factors: 1) what the founders think their company is worth, largely based on competitors, 2) actual revenue growth or potential thereof, 3) protection clauses for investors in case things head south (more on this later!), and 4) straight-up FOMO (fear of missing out). And they’re being serious.

Slow-Gallop Towards an Exit

In particular, 2015 provided a breeding ground for unicorns. Super low interest rates and outrageous amounts of capital allowed companies to simmer, hosting several rounds of private funding and increasing valuation. So, once a company reaches their desired valuation, what happens? As this TechCrunch article explains, start-ups generally have four outcomes: get acquired, go public, stay private, or flame out. Hint: nobody likes the last one. So, let’s discuss the first three…

- Get Acquired: You know this drill; this is the kind of deal that gets your prospect on the Forbes So in development, we love when companies get acquired. This option seems to be the one that has investors the giddiest. We’ve seen a couple success stories (most notable, Facebook’s acquisition of WhatsApp and Google’s $3 billion acquisition of Nest), with even non-tech companies getting in on the action this year (Walmart, Home Depot, etc.).

- Go Public: Historically, this has been the most favorable exit strategy. However, 2015 saw a pretty steep halt with just 23 tech IPOs raising a total of $4.2 billion, down from the 55 firms that raised $32.3 billion a year earlier. With recent regulation, such as Sarbanes-Oxley and the 2012 JOBS Act, it’s just easier for companies to stay private. Another issue here is once your company has high valuation, there is concern an IPO may not actually produce the market cap. In fact, almost 30 percent of unicorns floated with a lower valuation than promised last year (think: Square). That’s not to say they won’t rebound; Facebook certainly did, and look how well that’s turned out.

- Stay Private: As The Telegraph reports, while Amazon and Yahoo! floated at less than $500 million in the Nineties, it’s just not necessity today. Historically, IPOs have helped startups do three things: raise capital, provide liquidity, and legitimize the company. Today, start-ups can do all that and still remain private. Many are now hosting what’s been deemed a “private IPO.” Using this model, firms are raising un-heard-of levels of late-round capital. This has allowed companies like Uber and Airbnb (the source of long-awaited IPO whispers) not to float, when in years-past they would have by now. The issue here is eventually they have to turn a profit.

The Billion Dollar Question: How do they actually make money?

So, private or public, to be a unicorn, you should make money, right? Well… that my friends, is the billion-dollar question. As it turns out, there are a few ways a majority of tech firms bring in revenue. This interactive graphic, conceptualized by SEER Interactive and designed by O3 World, describes how popular Internet companies do just that. Generally, there are five options:

- Advertising: The most recognized way to add revenue is by selling ad space. Twitter has historically made up to 85 percent of its revenue this way. In 2015, Instagram and Pinterest both widened their ad buying to all business markets. Interestingly enough, the advertising market has become so huge that entire new unicorns are being birthed to help companies manage it.

- Subscribers: Companies like Netflix – and its rivals Amazon and Hulu – plan on becoming profitable through subscription fees, with Netflix expanding globally and promising to be profitable by 2017. But, that takes a lot of subscribers, and they’re still not there yet. So, it looks like you can thank investors for your “Making a Murderer” binge, not your $9.99.

- Freemium Services: Similar to the subscriber model, a company provides a base service and then charges a fee for premium features. Think Dropbox, Evernote, Hootsuite, and the list goes on and on. Outside of advertising, this has become the most dominant model (and arguably, the most successful) for our tech friends.

- Lead Generators and Partnerships: Here, firms receive an affiliate fee if a user purchases something from their site. So, when you log on to sites like Mint or Ravelry, they are literally banking on you signing up for a credit card or buying one of the crochet patterns they recommend.

- Royalties: This can really work two ways: a company can take a percentage of each transaction (like when you buy an app) or companies can come to an agreed upon fee or percentage for use of its platform. For example, everyone’s favorite fruit, Apple, receives big bucks from Google to be iOS’s default search engine. Google, who’s main model is advertising, relies on this search traffic to boost their advertising rates, in turn making millions. It’s nice when we can work together!

When looking at a unicorn, it’s important to remember that companies combine these methods to drive revenue. For example, let’s look at one of my favorite companies: Spotify. The company is based on the freemium model, making about $2.4 billion in premium subscriptions. However, it uses advertising to produce income from its free tier. Most recently, it announced a new deal with Starbucks to take streaming into a retail setting in hopes of attracting premium customers. My guess is there are also royalties in play here, though the terms of the deal are being held close to the vest. Turns out, companies don’t like to talk about how much money they pay each other.

Major Gift Prospects: Swipe Right for Investors

So, what does all this mean for your development prospects? Who is making money, and who is not?

Earlier, I alluded to protection clauses being added into investment agreements, and as it turns out, this is key. As valuation soars, investors know there is a chance a company may not live up to their unicorn/decacorn status upon exit. And while investors like betting on unicorns, they don’t like losing money in the process. To entice funders and especially the old firms that generally provide late-round infusions (think: the Goldman Sachses of the world), companies are including insurance policies for investors – you’ll see them discussed as “senior liquidation” and “downside protection.”

- Senior liquidation means that funders get their money back before anyone else, often with a profit.

- Downside protection ensures a funder’s stake in the company and guarantees they would receive extra shares if a company floats at a lower valuation.

Essentially, these two types of insurance cover that fuzzy gray area I talked about earlier, where the valuation-magic happens. Funders also generally use a portfolio approach, meaning that even if one company doesn’t deliver, they could still see great returns elsewhere.

While these insurance policies may protect investors, what about the folks building the companies?

Perhaps not surprisingly, founders and senior level execs are being protected in ways similar to investors. However, employees pinning their hopes to a big payout at the exit may want to hold off on their excitement until they see if the company actually lives up to its valuation. While the protection clauses do just what they’re supposed to – protect investors – they also dilute the shares or options being offered as compensation to employees.

The good news is, we see founders making money – and donating it! Just take a look at the growing members on the Giving Pledge list and new foundations being set up like the recent announcement of Reed Hastings’ new education fund.

Where is all this going?

Well, that seems to be the big question of 2016… We live in exciting times! The optimists are saying that technology will keep these unicorns galloping. The pessimists are saying don’t let that bubble pop you on the way out.

So, what do you think? Are your fundraisers frantically scheduling meetings in Silicon Valley? Are unicorns here to stay or will they return to mythical status in 2016 and beyond?