As we watch the United Kingdom deal with the aftermath of last month’s vote to leave the European Union, those of us in the philanthropy sector wonder what the loss of EU funding will mean for charities reliant on that funding. I asked Ben Rymer to share his thoughts and research once again here on The Intelligent Edge to help us understand Brexit’s potential impact on philanthropy.

While uncertainty rules the day on Brexit’s effect on philanthropy, four things seem reasonable to expect in the wake of the British public’s vote on June 23rd to leave the European Union.

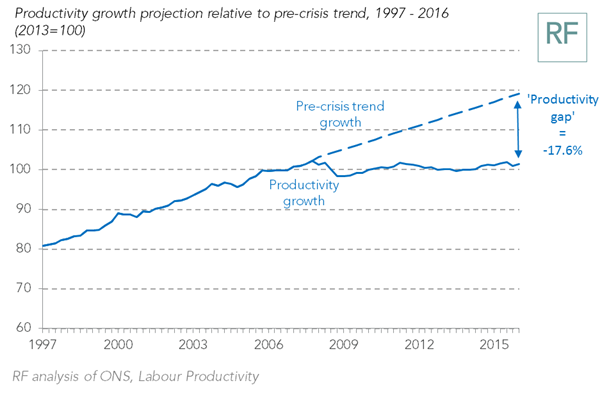

First, Brexit is likely to be bad news for the British macroeconomy. A weaker sterling (the British pound is so far the worst performing currency in the world in 2016), continuing low productivity (see chart below from the Resolution Foundation) and lower profits (the FTSE 250, consisting of mainly British companies, lost £38bn from June 24th-July 8th) are all notable trends.

There is a risk that Britain (or, in the event of a breakup of the UK, perhaps only England) will become a sort of ‘Greater Guernsey’.

Second, the scale of the threat to EU funding should not be underestimated. UK charities received more than £200m in EU funding in 2014, income which must surely be at high risk in the eventual occurrence of Brexit.

The journal Nature reported, “UK universities currently get around 16% of their research funding, and 15% of their staff, from the EU.” Science funding from the EU to UK universities alone is estimated to be more than £1 billion annually. Unless the UK government makes up that shortfall, the impact on charities that rely on scientific breakthroughs will be impacted for decades to come.

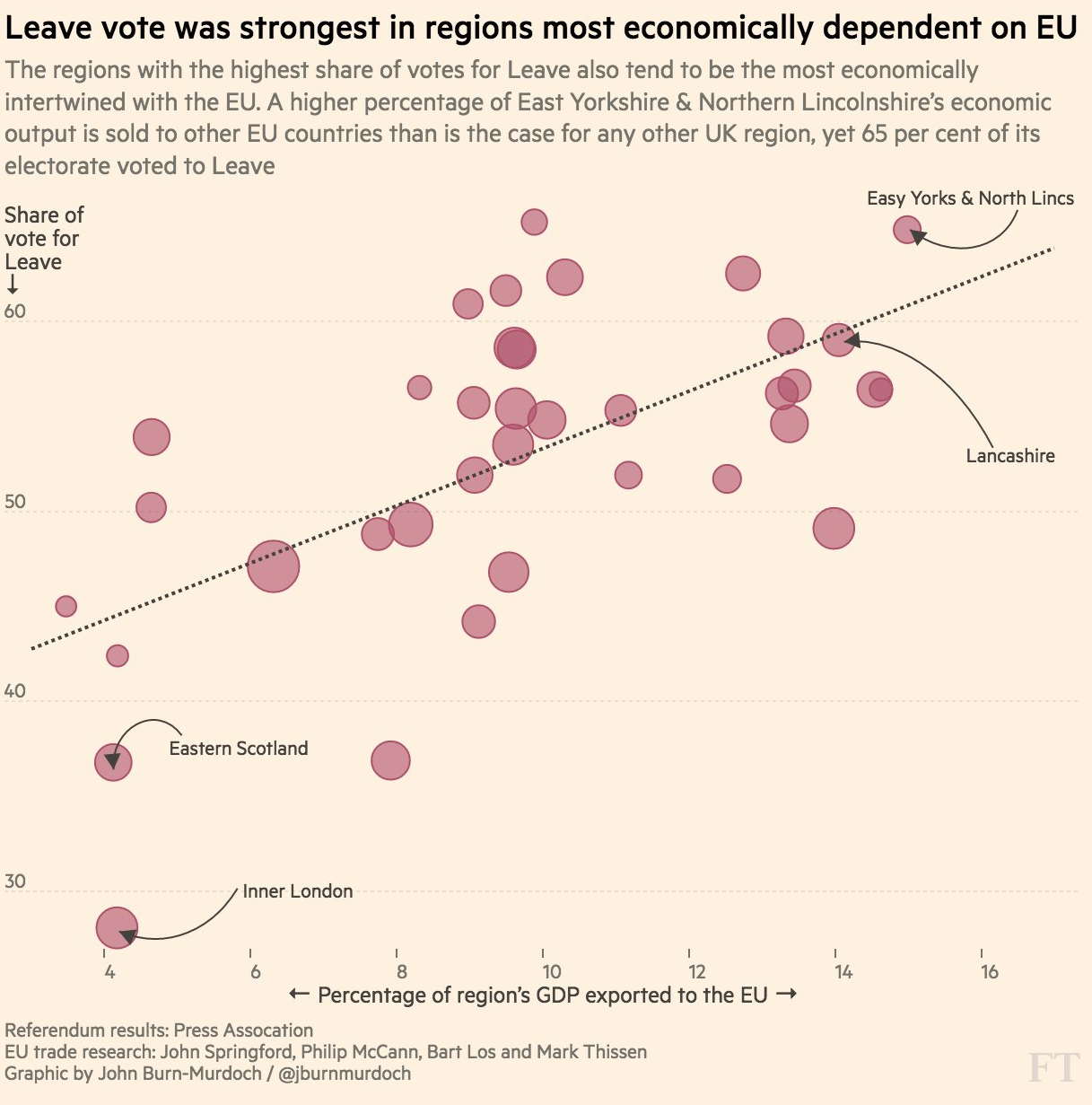

Paradoxically, as the Financial Times chart below shows, British “regions with the highest share of votes for Leave also tend to be the most economically intertwined with the EU”.

Third, some charitable sectors will suffer more than others. Arts & Heritage have been a major beneficiary of EU support; leaving the EU would impact this, as well as making the UK ineligible for major EU events such as as the European City of Culture, which was a boon for Liverpool, Britain’s most deprived city, when it held the accolade in 2008.

Finally, there will be a follow-on effect on the great British obsession – house prices. A fall in house prices will have a real impact on the value of residuary legacies, whose value is intrinsically related to property values.

Consider also that London is a hub of offshore finance, as this fascinating interactive Private Eye map makes clear, and so many London postcodes are majority offshore-owned. The effect on offshore finance, which, directly through investments in London real estate and indirectly through London’s status as one of the world’s largest offshore finance centres, could have a major effect on philanthropic giving. The ‘hidden wealth of nations has been a font of riches for the UK in recent decades; Brexit may see the fountain begin to dry up.

The real dangers, however, may not be immediately seen.

In the words of the British National Council for Voluntary Organisations (NCVO), “it is likely that the impact of Brexit in the short term will be over-estimated; but impact in the long-term will be under-estimated”.

A main plank of the Leave campaign was to roll back on ‘freedom of movement’, the EU principle that EU nationals are free to travel within the Union. But many major philanthropists – including Dame Vivien Duffield, Paul Hamlyn and the late Sir Naim Dangoor – to name a few – have described wanting to repay a debt to society as a motivation for their philanthropy. Fewer overseas nationals living in the UK will make such philanthropy rarer in future.

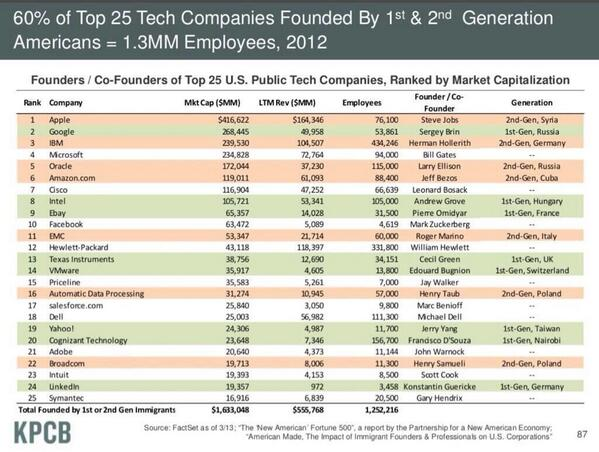

Business and livelihoods could also suffer – many big British and US employers were founded by migrants or their children. Here is the 2012 breakdown in the US according to management consulting firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield Byers:

As for the United Kingdom, in 2014, the Financial Times reported:

“Migrant entrepreneurs have created one in every seven UK companies, according to the first comprehensive analysis of official data about founder origins.

Almost half a million people from 155 countries have launched UK businesses that are currently trading with at least £1m in revenue, according to research by DueDil, a research company, and Centre for Entrepreneurs (CFE), a think-tank.

Together they are responsible for creating 14 per cent of British jobs.”

Wait and see

Britain is the first member state to vote to leave the Union, and as such Brexit represents uncharted waters for the EU. We wait to see whether the journey is plain sailing or stormy weather – for philanthropy and society more widely.

Ben is the Fundraising Research and Insight Manager at Age UK, the UK’s largest charity working with and for older people, where he has worked for five and a half years. Ben’s professional interest and specialism is in measuring affinity and gauging capacity to give using data. He blogs at (Fund) Raising Voices.

For further reading:

What Does Brexit Mean For Philanthropy? by Dr. Beth Breeze, Director of the University of Kent’s Centre for Philanthropy

A Fundraisers’s Response to Brexit by Susie Hills, Managing Director of Graham-Pelton Consulting

The Financial Times special section on the EU referendum